http://www.houstonchronicle.com/life/article/Pop-culture-applies-Woody-Guthrie-s-political-11961032.php

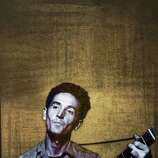

Pop culture applies Woody Guthrie’s political barbs masked in all-American balladry

August 25, 2017 Updated: August 26, 2017 11:01pm

“This land is your land, this land is my land,” sang Lady Gaga, reciting the lyrics of Woody Guthrie’s iconic “This Land Is Your Land” before plunging into Houston’s NRG Stadium as the Super Bowl halftime entertainment.

“This land was made for you and me.”

Gaga’s performance, against a backdrop of twinkling red, white and blue stars, might not have seemed political. The scene appeared to be nothing more than a singer performing a beloved song during the nation’s most popular sporting event.

During the previous year’s Super Bowl halftime show, Beyonce provoked viewers by trotting out a brigade of dancers dressed in Black Panther garb. It was interpreted by some as an anti-police statement. Lady Gaga was to be the nonpolitical sequel, an NFL-approved conciliator for both left and right. Yet she made her own statement, in the lyrics of Guthrie’s seemingly benign folk song. In other words, commentators were correct in interpreting Lady Gaga’s Guthrie reference as an indirect barb at President Donald Trump.

Today there exists a misconception that “This Land Is Your Land” is uncomplicatedly patriotic, an ode to the American prosperity that stretches “from California to New York Island.” Taught in elementary schools, the song sounds, well, nice, as if it were the musical equivalent of open arms or a hearth. But Lady Gaga couldn’t have made a more loaded choice that night. If he were living today, Guthrie might be the most pointed critic of the nation’s state of affairs.

In 2017, with the country in an existential crisis, with disparate factions fighting over what is or isn’t “American,” the man behind “This Land Is Your Land” remains essential. Compare his songs to the most biting protest anthems in music today – A Tribe Called Quest’s “We the People,” Janelle Monae’s “Hell You Talmbout” and much of Kendrick Lamar’s ouevre – and Guthrie, placed in a contemporary context, remains one of the country’s most acerbic poets of the political consciousness.

Simply put: Guthrie disagreed with nearly all politicians and capitalists.

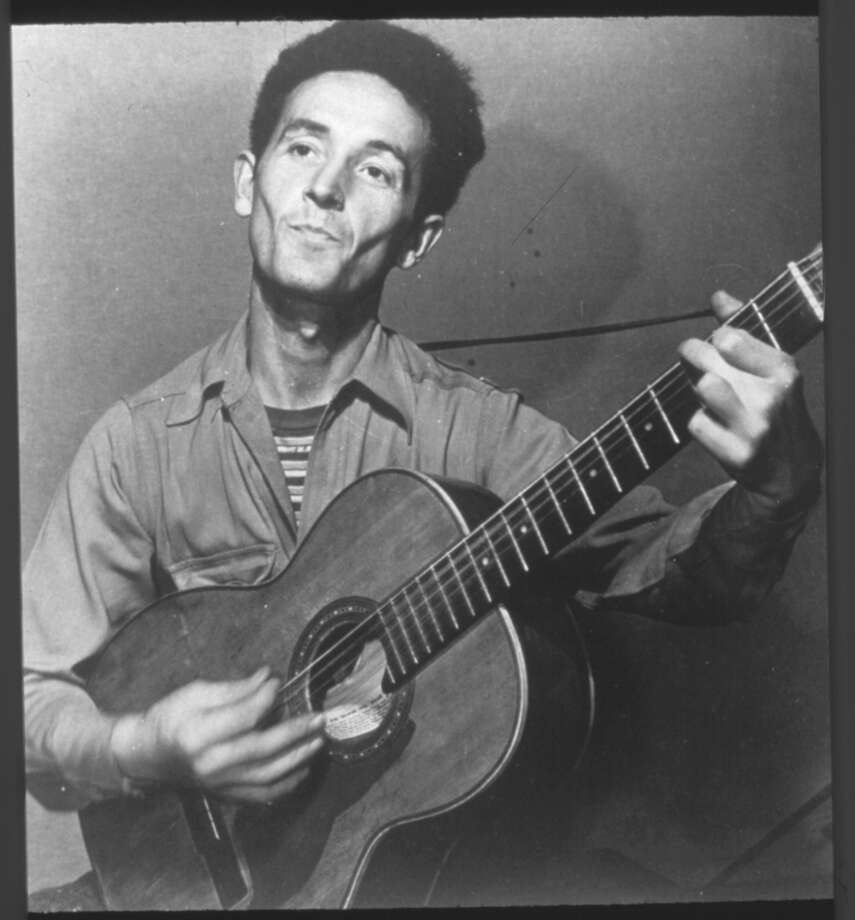

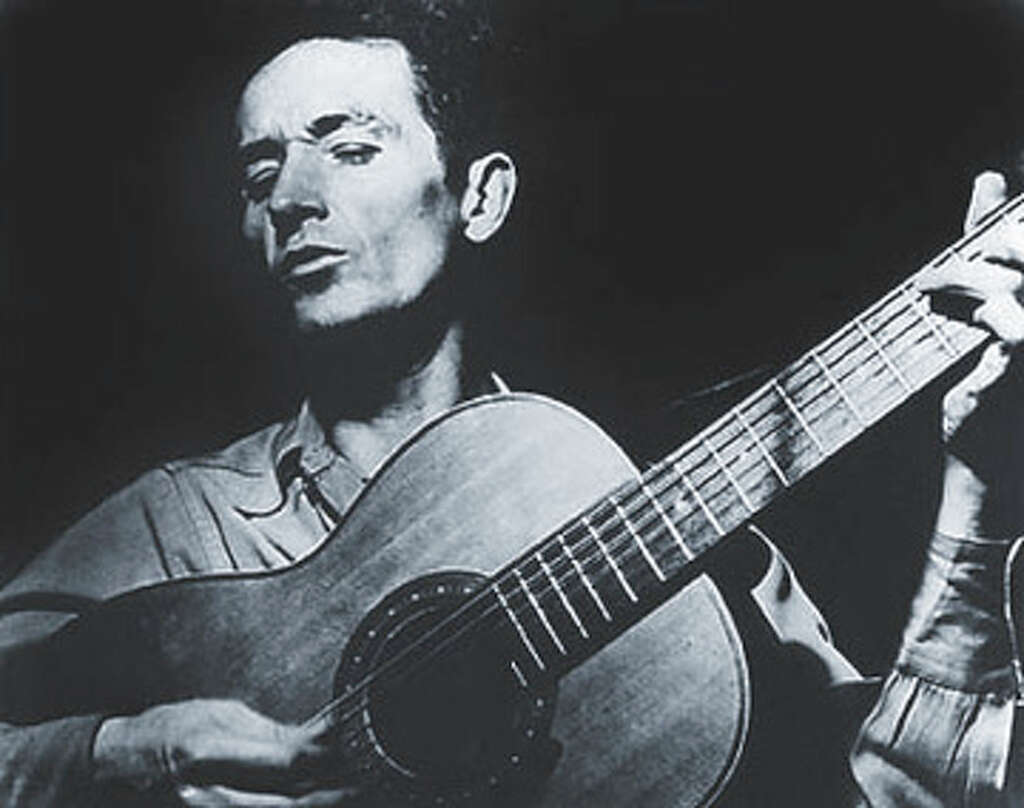

Consider, for example, that even presentations of his music that celebrate everything else about him – the charming hobo act, the man-of-the-people Midwestern modesty, the lulling, folksy chords of his songs – carry elements of subversion.

The first scene in “Woody Sez,” a buoyant and well-timed Guthrie tribute show at Stages Repertory Theatre through Sept. 3, has a working-class Okie approach a mic to sing “God Bless America” for a New York radio show in 1940, except he tells the audience he has a better song. He sings these lyrics to “This Land Is Your Land”:

In the shadow of the steeple

By the relief office I’d seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?

The official recording of “This Land Is Your Land” omits this verse, which has made Guthrie’s song seem more optimistic about America than he might have intended. “This land was made for you and me” suggests America offers opportunity for all of its citizens.

But the same idea, posed as a question, raises an eyebrow at American exceptionalism, suggesting this is a land of the poor and powerless as much as of the prosperous.

Guthrie’s image of the poor, standing hungry outside the relief office, isn’t the harshest damnation of American capitalism in the song. He also wrote this verse:

There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me.

The sign was painted, it said “Private Property.”

But on the back side, it didn’t say nothing.

This land was made for you and me.

It’s one of Guthrie’s most brilliant illustrations of privilege: a barrier, presumably owned by a corporation, that separates the haves and the have-nots. The connection to Trump’s “Build the Wall” campaign is easy, but imprecise – the verse’s political message points to economic, not literal barriers.

Born into a white middle-class family in Okemah, Okla., Guthrie wrote “Old Man Trump” in the ’50s as a response to living as a tenant of President Donald Trump’s father, Fred Trump, whom Guthrie despised for his discriminatory housing policies:

I suppose Old Man Trump knows just how much racial hate

He stirred up in that bloodpot of human hearts

When he drawed that color line

Here at his Beach Haven family project.

“Woody Sez,” devised by David M. Lutken with Nick Corley, features the superb Ben Hope, who blends country twang with pop clarity in his rendition of Guthrie. The musical tells Guthrie’s story, birth to death, in the form of a Wikipedia-biography-meets-greatest-hits-collection.

Eschewing the life of a “rock star,” the singer paid dearly for refusing to censor himself, getting kicked out of radio shows and spending years wandering the country. He wrote a column, titled “Woody Sez,” in the communist paper People’s World, as well as drew anti-capitalist cartoons. His songs frequently skewer bankers and other players of capitalism. As a migrant farm worker, he saw firsthand the cruelties of the age of industry.

Again and again, we see Guthrie run into trouble for his communist ideals. But his beliefs make sense.

If his earthy, blue-collar lyrics ring truer than those of wealthy modern-day country artists, so do his class-based protestations hit harder than the criticisms of America in, say, Beyoncé’s “Formation,” which described money as a form of power rather than corruption. When it comes to money (and not race), Guthrie’s the anti-establishment Bernie Sanders, Beyoncé’s the 1-percenter Hillary Clinton. And compared to even his best-known proteges, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan, Guthrie remains the least self-introspective and most invested in acting as a poet of the people, and not just for the people of his time.

By the end of “Woody Sez,” it’s clear Guthrie would not only have despised Trump but likely would have penned song after song in protest of him. That would have sung louder, and with more political clarity, than any tribute or quotation.

And though “Woody Sez” doesn’t shy from politics, the politics are secondary to the music in the show. Lady Gaga knew that but also realized not enough people would understand the implication of a Guthrie reference to get her in trouble – sideways commentary custom-made for keeping good PR in today’s outrage culture.

Consider, even, Stages Repertory Theatre artistic director Kenn McLaughlin’s sly suggestion of Guthrie’s politics without actually saying it:

“The whimsical musicianship inspired by much of Woody’s music and the camaraderie of a small ensemble act as metaphor for the larger promise of America’s unity,” he writes in his director’s note. “It isn’t so much political theatre as it is theatre beyond politics.”

McLaughlin is like Lady Gaga. He’s aware of the optics of staging a show about a staunch leftist during the age of Trump, but he avoids making his show partisan by suggesting Guthrie has a universal, “post-political” appeal.

The image of Guthrie as an all-American balladeer, who spoke to everyone, isn’t far off from the songwriter’s down-to-earth populism. Yet McLaughlin’s playbill writing can’t help but hide the controversial message in plain sight. Words like “promise” suggest an equality that doesn’t yet exist.

Guthrie, with his workaday attire and Okie accent, appears harmless. “This Land Is Your Land” sounds harmless. Lady Gaga’s performance seemed simply patriotic. McLaughlin’s message seems to be one of unity. But these are just appearances. Dig a little deeper and Guthrie’s harshest criticisms of American government, capitalism and idealism sound bitterly timely. Soon you realize “This land was made for you and me” was never anything more than a promise.

In the shadow of the steeple

By the relief office I’d seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there wondering,

Is this land made for you and me?

One of the lost verses to ‘This Land Is Your Land’