-

3 February 2016

- From the section US Election 2016

Though a Frenchman was the first person to describe America as “exceptional” and a Soviet, Joseph Stalin, inadvertently helped popularise the phrase “American exceptionalism” – he called it a “heresy” – the notion the United States is not just unique but superior has long been an article of national faith.

Writing in Democracy in America, which set out to explain why the American Revolution had succeeded while the French Revolution had failed, Alexis de Tocqueville observed Americans were “quite exceptional”, by which he meant different rather than better.

Over the centuries, however, the idea has taken hold here that America is liberty’s staunchest defender, democracy’s greatest exemplar and home to the usually brave – a country like no other.

That America has emerged as the leader of the free world is not regarded as some cosmic fluke.

Its global role and mission, a responsibility to spread American values around the world, was divinely sanctified and historically preordained, thanks to the genius of its founding fathers.

Jefferson’s “empire of liberty”, Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy”, and Reagan’s “shining city upon a hill” are variants on the same theme of American pre-eminence, a country that sought to colonise the planet with its ideas.

Image copyright AP

Image copyright AP Losing faith

Early in his presidency, Barack Obama looked set to retire the rhetoric of exceptionalism, even though many in America and around the world regarded his election, after the shocks of 9/11 and the Great Recession, as proof of its salience.

“I believe in American exceptionalism,” he told a journalist in 2009 during a visit to Strasbourg, “just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.”

Now, though, his speeches are essays in exceptionalist thinking, even if qualified with reminders about the constraints of US power and his personal preference for multilateral co-operation.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters The problem, globally, is that American exceptionalism has increasingly come to have negative connotations.

The hitch, domestically, is that Americans seem to be losing faith in the American system and American dream, hence the rise of populists like Bernie Sanders on the left and Donald Trump on the right.

Consider the face that America has recently presented to the rest of the world.

The frontrunner in the race for the Republican nomination has called for almost a quarter of the world’s population to be barred temporarily from entering the country, a nativist cry that has boosted Donald Trump’s popularity.

America’s Grand Old Party has been in a state of open civil war.

The idea of a Clinton restoration has failed to generate much enthusiasm – to many it smacks of a country going backward not forward, despite its promise of a female first.

The campaign, rather than being a beacon of democracy, has often been a viral joke.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Hollywood controversy

Then, look beyond the campaign trail.

Flint, Michigan, a city poisoned by its drinking water, is a story one would ordinarily expect to cover in the developing world in a failed state.

The Netflix global sensation Making a Murderer has put the US criminal justice system in the dock.

The Oregon militia stand-off has echoes of the lawless Wild West.

Before the monster blizzard closed much of the north-eastern US, Washington was brought to a standstill by an inch of snow.

Days later, the federal government remained shut down.

The Big Short, a movie about the collapse of the subprime mortgage market and the avarice of the major US investment banks, is a reminder of the excesses of Wall Street, and the fact just one person was prosecuted following the 2008 financial collapse.

Even Hollywood’s great shop window, the Academy Awards, has been mired in controversy over its “whites-only” nominations.

Image copyright Paramount Pictures via AP

Image copyright Paramount Pictures via AP American exceptionalism itself has something of a Sunset Boulevard feel to it, a black comedy where a faded silent movie star believes she is still the most luminous presence on the screen.

Nor is this merely a recent phenomenon.

In the run-up to the Iraq war, American exceptionalism smacked of imperial hubris.

In the chaotic aftermath, it was more a case of decline and fall.

The National Security Agency scandal has undercut America’s claim to have a clarion voice in international diplomacy.

Post-9/11, the detention centre at Guantanamo Bay has become as much a symbol of America to many in the world as the Statue of Liberty.

Systemic problems

After the massacre of schoolchildren in Newtown, and the epidemic of mass shootings elsewhere, American exceptionalism came to be equated with unchecked gun violence.

Image copyright AP

Image copyright AP Ferguson, and a spate of other police shootings of unarmed black men, has raised questions about the fairness of policing, a problem that seems especially pronounced here.

America also has the world’s highest incarceration rate, with 4.4% of the global population but 22% of its prisoners.

Putting so many people behind bars again seems uniquely American.

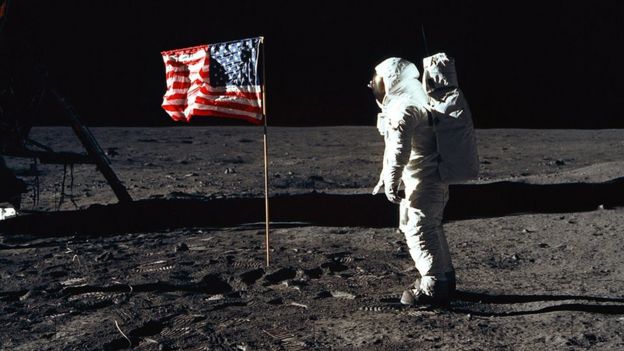

Even Nasa’s space programme no longer engenders the same worldwide awe as it did in its early days, when planting the Stars and Strips in the Sea of Tranquillity offered proof of exceptionalism, even as American GIs were mired in the quagmire of Vietnam.

Image copyright NASA

Image copyright NASA Many of the problems are systemic, arising from flaws in the democratic model that was supposed to offer a prototype.

Much of the gridlock in Washington stems from checks and balances that have come to be used as partisan weapons.

The constitution, an extraordinary document reflecting the brilliance of its authors, looks, to many, out of date.

In this age of mass shootings, laws are still based on a document drafted in the era of the single-shot musket.

The oddities of Campaign 2016 stem, as I argued last month, partly from the quirks and oddities of the electoral process.

Fortress America

As for spreading American values around the world, many people here simply don’t think it is worth the expenditure of blood and treasure, especially after draining wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Wanting America to be great again, the slogan of Donald Trump that often sparks chants of “USA, USA, USA”, is not the same as embracing exceptionalism, an implicitly interventionist creed.

The mood is more Fortress America, a bunker mentality.

Besides, there have always been Americans, especially on the left, who roll their eyes at the mere mention of exceptionalism.

For them it sounds arrogant, bullying, embarrassing.

Plainly, America can still boast pre-eminence in many realms.

It is militarily, culturally and financially dominant.

Impressive still are its powerhouse universities, its tech hubs and elite hospitals.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters However, just as striking are the symbols of regression: its decrepit schools, creaking bridges and antique airports.

Fading dream

Travelling around the country, perhaps the most striking difference from when I lived in America 10 years ago is the lack of national self-belief – a sureness, a braggadocio, that gave American exceptionalism real resonance at home.

With middle-class incomes stagnant, and with so much wealth concentrated in the hands of the much-derided “One Per Cent”, the American dream just no longer seems to ring true for many families.

Certainly, it is harder these days to find parents who believe, with absolute conviction, their children will enjoy lives of greater abundance.

Once, that truth was held to be self-evident.

Image copyright AP

Image copyright AP To many American readers, I know, this will all reek of the kind of European condescension that has doubled as commentary since the founding days of the Republic – Americans are not the only people with a sense of their superiority.

All I would say is I write as a long-time admirer: someone who at various stages of my life – as a schoolboy, as a student here, and as a young correspondent – has acted out my own version of the American Dream, at times with unblinking eyes.

While still seductive, while still thrilling, these days, I find the United States harder, as an outsider, to love.

For these are times when “Only in America” is increasingly used as a term of derision, and “American exceptionalism” sounds like an empty boast.