Why are Americans so angry?

-

3 hours ago

- From the section Magazine

Image copyright iStock

Image copyright iStock Americans are generally known for having a positive outlook on life, but with the countdown for November’s presidential election now well under way, polls show voters are angry. This may explain the success of non-mainstream candidates such as Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Bernie Sanders. But what is fuelling the frustration?

A CNN/ORC poll carried out in December 2015 suggests 69% of Americans are either “very angry” or “somewhat angry” about “the way things are going” in the US.

And the same proportion – 69% – are angry because the political system “seems to only be working for the insiders with money and power, like those on Wall Street or in Washington,” according to a NBC/Wall Street Journal poll from November.

Many people are not only angry, they are angrier than they were a year ago, according to an NBC/Esquire survey last month – particularly Republicans (61%) and white people (54%) but also 42% of Democrats, 43% of Latinos and 33% of African Americans.

Candidates have sensed the mood and are adopting the rhetoric. Donald Trump, who has arguably tapped into voters’ frustration better than any other candidate, says he is “very, very angry” and will “gladly accept the mantle of anger” while rival Republican Ben Carson says he has encountered “many Americans who are discouraged and angry as they watch the American dream slipping away”.

Democratic presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders says: “I am angry and millions of Americans are angry,” while Hillary Clinton says she “understands why people get angry”.

Here are five reasons why some voters feel the American dream is in tatters.

1. Economy

Although the country may have recovered from the recession – economic output has rebounded and unemployment rates have fallen from 10% in 2009 to 5% in 2015 – Americans are still feeling the pinch in their wallets. Household incomes have, generally speaking, been stagnant for 15 years. In 2014, the median household income was $53,657, according to the US Census Bureau – compared with $57,357 in 2007 and $57,843 in 1999 (adjusted for inflation).

There is also a sense that many jobs are of lower quality and opportunity is dwindling, says Galston. “The search for explanations can very quickly degenerate into the identification of villains in American politics. On the left it is the billionaires, the banks, and Wall Street. On the right it is immigrants, other countries taking advantage of us and the international economy – they are two sides of the same political coin.”

2. Immigration

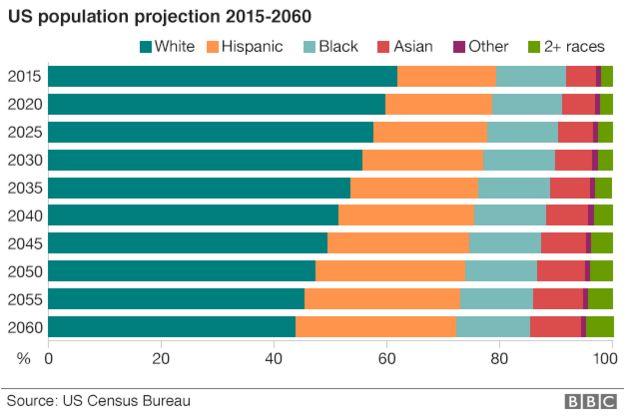

America’s demographics are changing – nearly 59 million immigrants have arrived in the US since 1965, not all of whom entered the country legally. Forty years ago, 84% of the American population was made up of non-Hispanic white people – by last year the figure was 62%, according to Pew Research. It projects this trend will continue, and by 2055 non-Hispanic white people will make up less than half the population. Pew expects them to account for only 46% of the population by 2065. By 2055, more Asians than any other ethnic group are expected to move to US.

“It’s been an era of huge demographic, racial, cultural, religious and generational change,” says Paul Taylor, author of The Next America. “While some celebrate these changes, others deplore them. Some older, whiter voters do not recognise the country they grew up in. There is a sense of alien tribes,” he says.

The US currently has 11.3 million illegal immigrants. Migrants often become a target of anger, says Roberto Suro, an immigration expert at the University of Southern California. “There is a displacement of anxiety and they become the face of larger sources of tensions, such as terrorism, jobs and dissatisfaction. We saw that very clearly when Donald Trump switched from [complaining about] Mexicans to Muslims without skipping a beat after San Bernardino,” he says, referring to the shooting in California in December that left 14 people dead.

3. Washington

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images When asked if they trust the government, 89% of Republicans and 72% of Democrats say “only sometimes” or “never”, according to Pew Research. Six out of 10 Americans think the government has too much power, a survey by Gallup suggests, while the government has been named as the top problem in the US for two years in a row – above issues such as the economy, jobs and immigration, according to the organisation.

The gridlock on Capitol Hill and the perceived impotence of elected officials has led to resentment among 20 to 30% of voters, says polling expert Karlyn Bowman, from the American Enterprise Institute. “People see politicians fighting and things not getting done – plus the responsibilities of Congress have grown significantly since the 1970s and there is simply more to criticise. People feel more distant from their government and sour on it,” she says.

William Galston thinks part of the appeal of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders is down to frustration with what some see as a failing system. “So on the right you have someone who is running as a ‘strong man’, a Berlusconi and Putin, who will get things done, and on the left you have someone who is rejecting incrementalism and calling for a political revolution,” he says.

Ted Cruz, who won the Republican caucuses in Iowa, is also running as an anti-establishment candidate. “Tonight is a victory for every American who’s watched in dismay as career politicians in Washington in both parties refuse to listen and too often fail to keep their commitments to the people,” he said on Monday night.

4. America’s place in the world

Image copyright AFP

Image copyright AFP America is used to being seen as a superpower but the number of Americans that think the US “stands above all other countries in the world” went from 38% in 2012 to 28% in 2014, Pew Research suggests. Seventy percent of Americans also think the US is losing respect internationally, according to a 2013 poll by the centre.

“For a country that is used to being on top of the world, the last 15 years haven’t been great in terms of foreign policy. There’s a feeling of having been at war since 9/11 that’s never really gone away, a sense America doesn’t know what it wants and that things aren’t going our way,” says Roberto Suro. The rise of China, the failure to defeat the Taliban and the slow progress in the fight against the so-called Islamic State group has contributed to the anxiety.

Americans are also more afraid of the prospect of terrorist attacks than at any time since 9/11, according to a New York Times/CBS poll. The American reaction to the San Bernardino shooting was different to the French reaction to the Paris attacks, says Galston. “Whereas the French rallied around the government, Americans rallied against it. There is an impression that the US government is failing in its most basic obligation to keep country and people safe.”

5. Divided nation

Image copyright iStock

Image copyright iStock Democrats and Republicans have become more ideologically polarised than ever. The typical (median), Republican is now more conservative in his or her core social, economic and political views than 94% of Democrats, compared with 70% in 1994, according to Pew Research. The median Democrat, meanwhile, is more liberal than 92% of Republicans, up from 64%.

The study also found that the share of Americans with a highly negative view of the opposing party has doubled, and that the animosity is so deep, many would be unhappy if a close relative married someone of a different political persuasion.

This polarisation makes reaching common ground on big issues such as immigration, healthcare and gun control more complicated. The deadlock is, in turn, angering another part of the electorate. “Despite this rise in polarisation in America, a large mass in the middle are pragmatic. They aren’t totally disengaged, they don’t want to see Washington gridlocked, but they roll their eyes at the nature of this discourse,” says Paul Taylor. This group includes a lot of young people and tends to eschew party labels. “If they voted,” he says, “they could play an important part of the election.”

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine’s email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.