-

3 hours ago

- From the section Magazine

by James Thompson

The primary season for the presidential election is currently in full swing now. No one can deny it.

At this point, it becomes important to try to understand the complexities involved in the current electoral cycle. The bourgeois media, the bourgeois candidates and every other talking head in this bourgeois society in which we reside does everything they can to obfuscate the electoral process. Their motto seems to be “Keep them ignorant, barefoot and vulnerable” to everything we throw at them.

This article will be an attempt to clarify the situation so that working people can make an educated choice.

After listening to many of the debates, both Democratic Party and Republican party, it becomes clear that all candidates are united in supporting the bourgeoisie, who ultimately bankroll the election campaigns. Not a single Democratic Party candidate or Republican Party candidate opposes imperialism in any way.

Lenin characterized Imperialism is the highest form of capitalism. As an update, we should recognize that Fascism/Nazism is the highest form of Imperialism.

Imperialism is the ignored Elephant in the Room.

All of the US Candidates for president advocate “American exceptionalism” which is a code word for US superiority. This right wing, fascistic, ideology has provided the momentum for the interventionistic tactics of the US government around the world. Millions of working people have been slaughtered as a result of this contemporary adaptation of the British notion of the “divine right of kings.” Students of history know full well that when one society claims superiority, they condemn their working people to ruination. Working people never claim superiority. The bourgeoisie always claim superiority.

Students of history know well the consequences of such a worldview. No one can question the catastrophe which befell the Roman empire or the 1000 year Reich.

Although there is not much difference between the major candidates for the office of President of the United States (POTUS), some differences are noteworthy.

Although this is oversimplified, this is one model for viewing the current candidates for POTUS.

All candidates, both Democratic Party and Republican Party are full-blown imperialists. They advocate the superiority of the USA. They suggest that the US military should dominate the globe without regard for the consequences that the US military personnel should suffer to say nothing for the slaughter of foreign nationals.

The US military has exerted its domination expressed as slaughter of civilians in countries too numerous to elaborate but include: India, Greece, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Iran, Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and all of Latin America. You get the picture.

Back to the candidates for POTUS.

Bernie Sanders advocates catching up with the European working class in terms of benefits. He endorses the crazy, paranoid, norm of military provocation abroad.

Hillary Clinton advocates that catching up with the European working class is too good for working Americans. She does not seem to want to agitate her bourgeois benefactors. In the middle of the electoral campaign, she does not want to ruffle the feathers of the bourgeoisie. She does not want to seem to place in jeopardy her donations from the ultra-wealthy. At the same time, she exemplifies the meaning of mendacity. She paints herself as a realist when in fact she is a trusted drum girl for the bourgeoisie. She advocates “All power to the bourgeoisie!”

The Republican candidates all are avid imperialists/fascists. They proclaim American superiority without blushing. They advocate war without brains. They advocate no regulation for the bourgeoisie and simultaneously want to trash education, healthcare and any other social network benefits for working people and their families. Their motto is “You’re fired!”

Voters in the US have a clear choice in the current electoral cycle. They can choose the “United States of Anger” and vote for Bernie Sanders. They can choose the “United States of Apathy” and vote for Hillary Clinton. They can choose the “United States of Arrogance” and vote for any of the Republican candidates.

It appears likely that given the degenerate political candidates, working people will choose the “United States of Anarchy.” This bodes well for Hillary Clinton.

Eventually, working people will seize the reins of political power from the bourgeoisie and establish a worker’s democracy. No one knows if this will happen in our lifetime.

Image copyright iStock

Image copyright iStock Americans are generally known for having a positive outlook on life, but with the countdown for November’s presidential election now well under way, polls show voters are angry. This may explain the success of non-mainstream candidates such as Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Bernie Sanders. But what is fuelling the frustration?

A CNN/ORC poll carried out in December 2015 suggests 69% of Americans are either “very angry” or “somewhat angry” about “the way things are going” in the US.

And the same proportion – 69% – are angry because the political system “seems to only be working for the insiders with money and power, like those on Wall Street or in Washington,” according to a NBC/Wall Street Journal poll from November.

Many people are not only angry, they are angrier than they were a year ago, according to an NBC/Esquire survey last month – particularly Republicans (61%) and white people (54%) but also 42% of Democrats, 43% of Latinos and 33% of African Americans.

Candidates have sensed the mood and are adopting the rhetoric. Donald Trump, who has arguably tapped into voters’ frustration better than any other candidate, says he is “very, very angry” and will “gladly accept the mantle of anger” while rival Republican Ben Carson says he has encountered “many Americans who are discouraged and angry as they watch the American dream slipping away”.

Democratic presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders says: “I am angry and millions of Americans are angry,” while Hillary Clinton says she “understands why people get angry”.

Here are five reasons why some voters feel the American dream is in tatters.

Although the country may have recovered from the recession – economic output has rebounded and unemployment rates have fallen from 10% in 2009 to 5% in 2015 – Americans are still feeling the pinch in their wallets. Household incomes have, generally speaking, been stagnant for 15 years. In 2014, the median household income was $53,657, according to the US Census Bureau – compared with $57,357 in 2007 and $57,843 in 1999 (adjusted for inflation).

There is also a sense that many jobs are of lower quality and opportunity is dwindling, says Galston. “The search for explanations can very quickly degenerate into the identification of villains in American politics. On the left it is the billionaires, the banks, and Wall Street. On the right it is immigrants, other countries taking advantage of us and the international economy – they are two sides of the same political coin.”

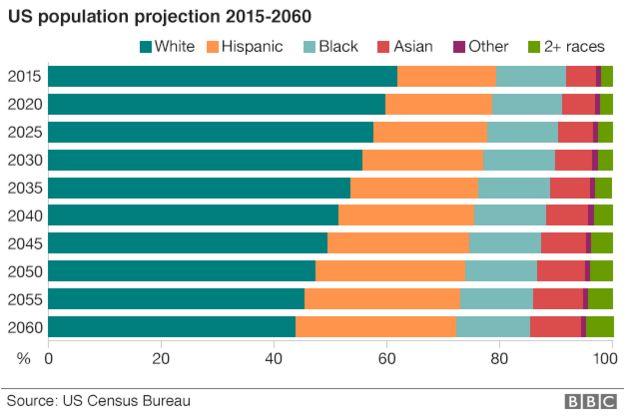

America’s demographics are changing – nearly 59 million immigrants have arrived in the US since 1965, not all of whom entered the country legally. Forty years ago, 84% of the American population was made up of non-Hispanic white people – by last year the figure was 62%, according to Pew Research. It projects this trend will continue, and by 2055 non-Hispanic white people will make up less than half the population. Pew expects them to account for only 46% of the population by 2065. By 2055, more Asians than any other ethnic group are expected to move to US.

“It’s been an era of huge demographic, racial, cultural, religious and generational change,” says Paul Taylor, author of The Next America. “While some celebrate these changes, others deplore them. Some older, whiter voters do not recognise the country they grew up in. There is a sense of alien tribes,” he says.

The US currently has 11.3 million illegal immigrants. Migrants often become a target of anger, says Roberto Suro, an immigration expert at the University of Southern California. “There is a displacement of anxiety and they become the face of larger sources of tensions, such as terrorism, jobs and dissatisfaction. We saw that very clearly when Donald Trump switched from [complaining about] Mexicans to Muslims without skipping a beat after San Bernardino,” he says, referring to the shooting in California in December that left 14 people dead.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images When asked if they trust the government, 89% of Republicans and 72% of Democrats say “only sometimes” or “never”, according to Pew Research. Six out of 10 Americans think the government has too much power, a survey by Gallup suggests, while the government has been named as the top problem in the US for two years in a row – above issues such as the economy, jobs and immigration, according to the organisation.

The gridlock on Capitol Hill and the perceived impotence of elected officials has led to resentment among 20 to 30% of voters, says polling expert Karlyn Bowman, from the American Enterprise Institute. “People see politicians fighting and things not getting done – plus the responsibilities of Congress have grown significantly since the 1970s and there is simply more to criticise. People feel more distant from their government and sour on it,” she says.

William Galston thinks part of the appeal of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders is down to frustration with what some see as a failing system. “So on the right you have someone who is running as a ‘strong man’, a Berlusconi and Putin, who will get things done, and on the left you have someone who is rejecting incrementalism and calling for a political revolution,” he says.

Ted Cruz, who won the Republican caucuses in Iowa, is also running as an anti-establishment candidate. “Tonight is a victory for every American who’s watched in dismay as career politicians in Washington in both parties refuse to listen and too often fail to keep their commitments to the people,” he said on Monday night.

Image copyright AFP

Image copyright AFP America is used to being seen as a superpower but the number of Americans that think the US “stands above all other countries in the world” went from 38% in 2012 to 28% in 2014, Pew Research suggests. Seventy percent of Americans also think the US is losing respect internationally, according to a 2013 poll by the centre.

“For a country that is used to being on top of the world, the last 15 years haven’t been great in terms of foreign policy. There’s a feeling of having been at war since 9/11 that’s never really gone away, a sense America doesn’t know what it wants and that things aren’t going our way,” says Roberto Suro. The rise of China, the failure to defeat the Taliban and the slow progress in the fight against the so-called Islamic State group has contributed to the anxiety.

Americans are also more afraid of the prospect of terrorist attacks than at any time since 9/11, according to a New York Times/CBS poll. The American reaction to the San Bernardino shooting was different to the French reaction to the Paris attacks, says Galston. “Whereas the French rallied around the government, Americans rallied against it. There is an impression that the US government is failing in its most basic obligation to keep country and people safe.”

Image copyright iStock

Image copyright iStock Democrats and Republicans have become more ideologically polarised than ever. The typical (median), Republican is now more conservative in his or her core social, economic and political views than 94% of Democrats, compared with 70% in 1994, according to Pew Research. The median Democrat, meanwhile, is more liberal than 92% of Republicans, up from 64%.

The study also found that the share of Americans with a highly negative view of the opposing party has doubled, and that the animosity is so deep, many would be unhappy if a close relative married someone of a different political persuasion.

This polarisation makes reaching common ground on big issues such as immigration, healthcare and gun control more complicated. The deadlock is, in turn, angering another part of the electorate. “Despite this rise in polarisation in America, a large mass in the middle are pragmatic. They aren’t totally disengaged, they don’t want to see Washington gridlocked, but they roll their eyes at the nature of this discourse,” says Paul Taylor. This group includes a lot of young people and tends to eschew party labels. “If they voted,” he says, “they could play an important part of the election.”

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine’s email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

Though a Frenchman was the first person to describe America as “exceptional” and a Soviet, Joseph Stalin, inadvertently helped popularise the phrase “American exceptionalism” – he called it a “heresy” – the notion the United States is not just unique but superior has long been an article of national faith.

Writing in Democracy in America, which set out to explain why the American Revolution had succeeded while the French Revolution had failed, Alexis de Tocqueville observed Americans were “quite exceptional”, by which he meant different rather than better.

Over the centuries, however, the idea has taken hold here that America is liberty’s staunchest defender, democracy’s greatest exemplar and home to the usually brave – a country like no other.

That America has emerged as the leader of the free world is not regarded as some cosmic fluke.

Its global role and mission, a responsibility to spread American values around the world, was divinely sanctified and historically preordained, thanks to the genius of its founding fathers.

Jefferson’s “empire of liberty”, Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy”, and Reagan’s “shining city upon a hill” are variants on the same theme of American pre-eminence, a country that sought to colonise the planet with its ideas.

Image copyright AP

Image copyright AP Early in his presidency, Barack Obama looked set to retire the rhetoric of exceptionalism, even though many in America and around the world regarded his election, after the shocks of 9/11 and the Great Recession, as proof of its salience.

“I believe in American exceptionalism,” he told a journalist in 2009 during a visit to Strasbourg, “just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.”

Now, though, his speeches are essays in exceptionalist thinking, even if qualified with reminders about the constraints of US power and his personal preference for multilateral co-operation.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters The problem, globally, is that American exceptionalism has increasingly come to have negative connotations.

The hitch, domestically, is that Americans seem to be losing faith in the American system and American dream, hence the rise of populists like Bernie Sanders on the left and Donald Trump on the right.

Consider the face that America has recently presented to the rest of the world.

The frontrunner in the race for the Republican nomination has called for almost a quarter of the world’s population to be barred temporarily from entering the country, a nativist cry that has boosted Donald Trump’s popularity.

America’s Grand Old Party has been in a state of open civil war.

The idea of a Clinton restoration has failed to generate much enthusiasm – to many it smacks of a country going backward not forward, despite its promise of a female first.

The campaign, rather than being a beacon of democracy, has often been a viral joke.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Then, look beyond the campaign trail.

Flint, Michigan, a city poisoned by its drinking water, is a story one would ordinarily expect to cover in the developing world in a failed state.

The Netflix global sensation Making a Murderer has put the US criminal justice system in the dock.

The Oregon militia stand-off has echoes of the lawless Wild West.

Before the monster blizzard closed much of the north-eastern US, Washington was brought to a standstill by an inch of snow.

Days later, the federal government remained shut down.

The Big Short, a movie about the collapse of the subprime mortgage market and the avarice of the major US investment banks, is a reminder of the excesses of Wall Street, and the fact just one person was prosecuted following the 2008 financial collapse.

Even Hollywood’s great shop window, the Academy Awards, has been mired in controversy over its “whites-only” nominations.

Image copyright Paramount Pictures via AP

Image copyright Paramount Pictures via AP American exceptionalism itself has something of a Sunset Boulevard feel to it, a black comedy where a faded silent movie star believes she is still the most luminous presence on the screen.

Nor is this merely a recent phenomenon.

In the run-up to the Iraq war, American exceptionalism smacked of imperial hubris.

In the chaotic aftermath, it was more a case of decline and fall.

The National Security Agency scandal has undercut America’s claim to have a clarion voice in international diplomacy.

Post-9/11, the detention centre at Guantanamo Bay has become as much a symbol of America to many in the world as the Statue of Liberty.

After the massacre of schoolchildren in Newtown, and the epidemic of mass shootings elsewhere, American exceptionalism came to be equated with unchecked gun violence.

Image copyright AP

Image copyright AP Ferguson, and a spate of other police shootings of unarmed black men, has raised questions about the fairness of policing, a problem that seems especially pronounced here.

America also has the world’s highest incarceration rate, with 4.4% of the global population but 22% of its prisoners.

Putting so many people behind bars again seems uniquely American.

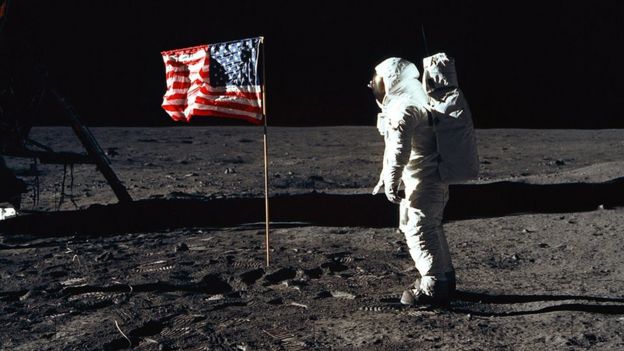

Even Nasa’s space programme no longer engenders the same worldwide awe as it did in its early days, when planting the Stars and Strips in the Sea of Tranquillity offered proof of exceptionalism, even as American GIs were mired in the quagmire of Vietnam.

Image copyright NASA

Image copyright NASA Many of the problems are systemic, arising from flaws in the democratic model that was supposed to offer a prototype.

Much of the gridlock in Washington stems from checks and balances that have come to be used as partisan weapons.

The constitution, an extraordinary document reflecting the brilliance of its authors, looks, to many, out of date.

In this age of mass shootings, laws are still based on a document drafted in the era of the single-shot musket.

The oddities of Campaign 2016 stem, as I argued last month, partly from the quirks and oddities of the electoral process.

As for spreading American values around the world, many people here simply don’t think it is worth the expenditure of blood and treasure, especially after draining wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images Wanting America to be great again, the slogan of Donald Trump that often sparks chants of “USA, USA, USA”, is not the same as embracing exceptionalism, an implicitly interventionist creed.

The mood is more Fortress America, a bunker mentality.

Besides, there have always been Americans, especially on the left, who roll their eyes at the mere mention of exceptionalism.

For them it sounds arrogant, bullying, embarrassing.

Plainly, America can still boast pre-eminence in many realms.

It is militarily, culturally and financially dominant.

Impressive still are its powerhouse universities, its tech hubs and elite hospitals.

Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters However, just as striking are the symbols of regression: its decrepit schools, creaking bridges and antique airports.

Travelling around the country, perhaps the most striking difference from when I lived in America 10 years ago is the lack of national self-belief – a sureness, a braggadocio, that gave American exceptionalism real resonance at home.

With middle-class incomes stagnant, and with so much wealth concentrated in the hands of the much-derided “One Per Cent”, the American dream just no longer seems to ring true for many families.

Certainly, it is harder these days to find parents who believe, with absolute conviction, their children will enjoy lives of greater abundance.

Once, that truth was held to be self-evident.

Image copyright AP

Image copyright AP To many American readers, I know, this will all reek of the kind of European condescension that has doubled as commentary since the founding days of the Republic – Americans are not the only people with a sense of their superiority.

All I would say is I write as a long-time admirer: someone who at various stages of my life – as a schoolboy, as a student here, and as a young correspondent – has acted out my own version of the American Dream, at times with unblinking eyes.

While still seductive, while still thrilling, these days, I find the United States harder, as an outsider, to love.

For these are times when “Only in America” is increasingly used as a term of derision, and “American exceptionalism” sounds like an empty boast.